She told me to not go see the 1978 movie, "Dawn of the Dead" but I did it anyway. And that was my first film exposure to the idea of "zombies" and again, the nightmares and gross images were consequences enough!

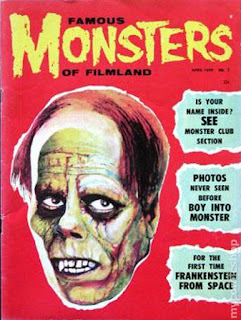

It took me by surprise, mainly because my early experiences with monster genre was the old "Monsters of Hollywood" magazine that was part of my weird kid experience growing up.

This magazine covered the original cinema explorations of Dracula, Frankenstein, and the werewolf. These were the now iconic figures made famous by Bela Lagosi, Boris Karloff, and Lon Cheney Jr.Wikipedia lists 567 films 'zombie' movies, but IMDB lists over 7900.

The basic premise of any zombie movie is an apocalyptic account of reanimated corpses who prey on human flesh. The cause of the reanimation is by many different means including: voodoo, radiation, parasites, bacteria, and fungi. The wikipedia article on the etymology of zombie is quite interesting.

Popular portrayals like "The Walking Dead" carry on the mainstream ideas that these zombies animate after death by means of some mysterious infection with an insatiable need for blood and guts. They are slow moving creatures who overwhelm by numbers and their bites spread the contagion.

I have friends and a few family members who have seen the newest version of this myth in the HBO series, 'The Last of Us' but I am not up on the details except these zombies have connection by way of fungal vines and they can run (I have always counted on outrunning them- so that stinks).

In the end, a zombie film is another type of science fiction where alternate realities explore issues of current society and human nature.

Human beings making choices within the pressures of life and death circumstances leaves no shortages of storylines. The complexities of relationships, attitudes, emotions, and actions are many times predictable but also have the wildcard moments of irrational or unexpected turns. Kind of like me and whether I listened to my mama or not.

In zombie mythology, human beings turn out to be much more dangerous than the 'walkers'.

The hints of truth in these myths and connection to real life human nature is what 'sells' us on the story lines even more than the suspenseful horror or action sequences. The meaning is there though we often pass by without giving it much thought.It's just a movie or show.... right? But what does tie us into following the narrative?

Why do we not care if a zombie gets whacked but grieve over a main character going down?

What hints make us 'trust' some of the human beings it the story but are skeptical of the motives of others?

What makes us label some characters as heroes but others as villains?

What makes us accept that characters can change in virtue of vice?

What gives us plausible acceptance when a characters acts contrary to their base nature? Why does a 'good' man do a 'bad' thing or vice versa?

In reality, the 'last of us' is just like the 'rest of us'.

As we encounter the many facets of life, we have to consider if there is actually a true narrative that allows all of the others to finally connect in a way that begs our attention and plays the various chords of emotions and responses we have as humans.

Is there one? Which one?

If you ever have time, I encourage you to read the many accounts of the famous conversation between C.S.Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien on Sept 19, 1931.

The two men with another friend, Hugo Dyson, took a stroll along 'Addison's Walk' in Oxford. Lewis found Tolkien likable but strange. How could a man of such great intellect still cling to something like old religious myths?

In the famous conversation, Lewis actually mentioned how much he loved 'myth', though he knew ultimately they were based on lies.

Tolkien countered Lewis by exploring the yearning men have for meaning and redemption. He also argued that many myths in global story-telling actually parallel Biblical accounts. Could the love we have for these stories actually point to something true?

If Jesus Christ was real in space, time, and history.. could there be something more in play here than just another mythological tale?

Lewis recounts that one conversation led to a later acceptance of the truth of the gospel after a motorcycle ride through the countryside where he pondered these points.

Here is how C.S. Lewis says it himself in God in the Dock (emphasis mine)

“Now as myth transcends thought, incarnation transcends myth. The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the dying god, without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens—at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences. We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle.”

“God is more than a god, not less; Christ is more than Balder, not less. We must not be ashamed of the mythical radiance resting on our theology. We must not be nervous about ‘parallels’ and ‘pagan Christs’: they ought to be there—it would be a stumbling block if they weren’t. We must not, in false spirituality, withhold our imaginative welcome. If God chooses to be mythopoeic—and is not the sky itself a myth—shall we refuse to be mythopathic? For this is the marriage of heaven and earth: perfect myth and perfect fact: claiming not only our love and our obedience, but also our wonder and delight, addressed to the savage, the child, and the poet in each one of us no less than to the moralist, the scholar, and the philosopher.”

No comments:

Post a Comment